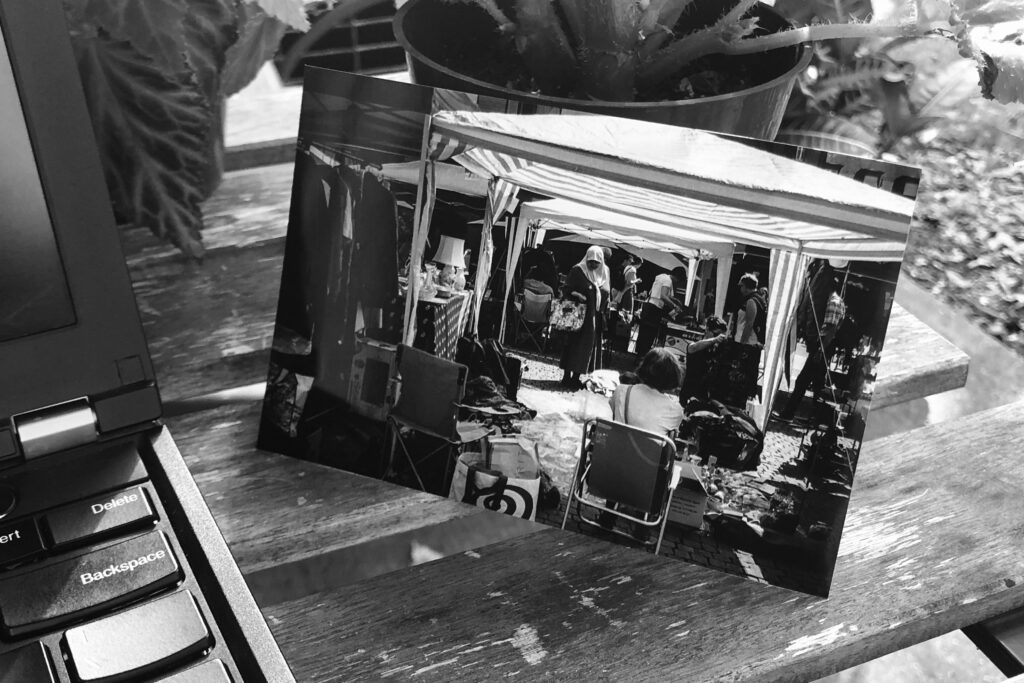

Saturday was the day of the wedding. I remember waking up somewhat later than normal. I cooked in my host’s kitchen and sat outside to enjoy my meal, a book I had brought with me, and the sounds of the morning. When I finally ventured out I was surprised to see that the winding streets and small open spaces, like the piazzas you might find in Italy, were flooded with people. The quiet city had turned into a bustling market. Everything imaginable was being sold. Amidst the hum of bargaining, the laughter of children, and the conversations mobile canopies sheltered both sellers and browsers, framed paintings, electronics, clothes, lamps, flowers, silverware, produce, rugs and other home furnishings.

The origin of the phrase flea market is difficult to trace. One theory suggests it grew from Manhattan’s 18th century Fly Market, from the Dutch word vly, meaning “valley,” on Maiden Lane which later became the Fulton Fish Market. Arguably the most popular theory was presented by Albert LaFarge in his well publicized article, What is a Flea Market? He traces the phrase back to the translation of a popular outdoor bazaar in Paris, marché aux puces, named after the small insects which were thought to infest the upholstery of used furniture being sold.

Another possible origin is that the plans of Georges-Eugene Haussmann, the architect of modern-day Paris, which saw the destruction of houses and building of wide thoroughfares for the military to march down forced many second-hand goods sellers to relocate. Despite this, they continued selling their goods in the north of Paris in front of the gate Porte de Clignancourt, an area well known today for its flea market, which spans seven hectares.

Perhaps, the true origin of the flea market would be more accurately translated as Le marché de ceux qui ont fui, the market of those who fled. I suppose that’s not very catchy though. I wonder if this is because we find bloodsucking pests more agreeable to reference than human displacement.